by Charles Lear, author of “The Flying Saucer Investigators.”

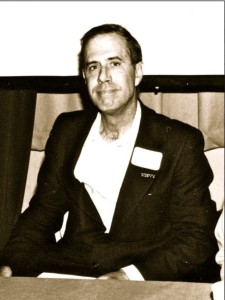

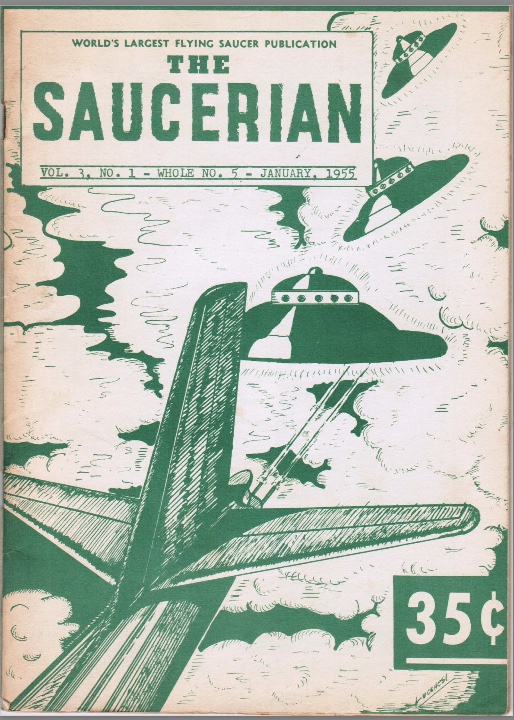

James W. Moseley was a part of the UFO scene from the days of the first private investigators in the early 1950s up until his death in 2012. He ran the longest running saucer group, the Saucer and Unexplained Celestial Events Research Society or S.A.U.C.E.R.S. (he and the group picked the acronym before they figured out what it could stand for) and steadily published a newsletter, known for most of its existence as Saucer Smear. Moseley has been called the Court Jester of UFOlogy due to his habit of poking fun at those who took themselves and the subject too seriously, and was involved in some hoaxes/pranks with his friend Gray Barker that became infamous. He wrote a book with Karl Pflock about his exploits in saucerdom that was published in 2002 titled Shockingly Close to the Truth: Confessions of a Grave-Robbing UFOlogist. In spite of his less-than-serious nature, he did do some serious investigation in his early days, and in one instance, looked into a saucer crash story and wrote an article about it that was published in the January 1955 issue of Gray Barker’s magazine, The Saucerian.

James W. Moseley was a part of the UFO scene from the days of the first private investigators in the early 1950s up until his death in 2012. He ran the longest running saucer group, the Saucer and Unexplained Celestial Events Research Society or S.A.U.C.E.R.S. (he and the group picked the acronym before they figured out what it could stand for) and steadily published a newsletter, known for most of its existence as Saucer Smear. Moseley has been called the Court Jester of UFOlogy due to his habit of poking fun at those who took themselves and the subject too seriously, and was involved in some hoaxes/pranks with his friend Gray Barker that became infamous. He wrote a book with Karl Pflock about his exploits in saucerdom that was published in 2002 titled Shockingly Close to the Truth: Confessions of a Grave-Robbing UFOlogist. In spite of his less-than-serious nature, he did do some serious investigation in his early days, and in one instance, looked into a saucer crash story and wrote an article about it that was published in the January 1955 issue of Gray Barker’s magazine, The Saucerian.

While Moseley came across the story only a few years after the news came out that the Army had recovered a disk at Roswell, that story went away after it was announced to the press that it was a weather balloon and only came to the attention of UFOlogists in the late 1970s after Stanton Friedman resurrected it. The crash story that caught everyone’s attention back in the 1950s was the alleged crash in Aztec, New Mexico, as recounted in the 1950 book by Frank Scully, Behind the Flying Saucers. While that story was discredited in the article by J.P. Cahn, “The Flying Saucers and the Mysterious Little Men” in the September 1952 issue of True magazine, it got rumors circulating that the U.S. government had saucers and alien bodies in its possession that it wasn’t telling the public about, and this story is possibly a product of that.

While Moseley came across the story only a few years after the news came out that the Army had recovered a disk at Roswell, that story went away after it was announced to the press that it was a weather balloon and only came to the attention of UFOlogists in the late 1970s after Stanton Friedman resurrected it. The crash story that caught everyone’s attention back in the 1950s was the alleged crash in Aztec, New Mexico, as recounted in the 1950 book by Frank Scully, Behind the Flying Saucers. While that story was discredited in the article by J.P. Cahn, “The Flying Saucers and the Mysterious Little Men” in the September 1952 issue of True magazine, it got rumors circulating that the U.S. government had saucers and alien bodies in its possession that it wasn’t telling the public about, and this story is possibly a product of that.

The headline of Moseley’s article reads, “Who’s lying? The Wright Field Story.” According to Moseley, he received a letter in April of 1954 in which the writer offered the opinion that the U.S. Air Force was “holding a saucer or parts thereof at Wright-Patterson Field.” According to the writer, his opinion was based mainly on the testimony of a woman who he said was a WAC at Wright Field in the fall of 1952 during a Red and White alert, (issued when a base is under threat of aerial attack) which in this instance lasted two weeks.

According to the writer, the woman learned that a saucer had been brought to Wright, and she saw a photo of it. The alert was out of fear that the captured saucer had sent a transmission and that there would be an attack. The writer wasn’t sure, but thought the saucer might have been recovered near Columbus, Ohio.

Moseley wrote that he’d “been making an intensive investigation of saucers for almost a year” when he got the letter and had come across rumors, “some stranger than this one,” concerning captured saucers with “little men from outer space found in them.” Other “rumors” that Moseley includes are: that an anthropology professor from Columbia went to examine the bodies, that a man in Florida talked to a man who knew of a man who drove an Army truck carrying a saucer that had crashed inside a nearby military base, and that a doctor had examined “little men” in a New York City funeral parlor.

Moseley wrote that he’d “been making an intensive investigation of saucers for almost a year” when he got the letter and had come across rumors, “some stranger than this one,” concerning captured saucers with “little men from outer space found in them.” Other “rumors” that Moseley includes are: that an anthropology professor from Columbia went to examine the bodies, that a man in Florida talked to a man who knew of a man who drove an Army truck carrying a saucer that had crashed inside a nearby military base, and that a doctor had examined “little men” in a New York City funeral parlor.

According to Moseley, the rumors were “un-checkable” or without evidence or were outright hoaxes. He attributed such tales as coming from Scully’s book and tells the reader that after the True magazine article, as of April that year he was of the opinion that the U.S. government “had no material evidence of the existence of saucers.”

Although the letter about the woman at Wright field didn’t impress him much, he visited the letter writer, whom he refers to as “Mr. X,” at his house and heard a tape of the woman, referred to as “Miss Y,” telling her story. According to Moseley, her sincerity impressed him, and he “decided that here at last was something concrete concerning captured saucers . . .”

Moseley wrote that he managed to locate Miss Y with only her first name and “three or four other facts about her” and that that story would make an interesting article in itself. He interviewed her and got her story, as opposed to Mr. X’s version of it, and discovered she did not work at Wright-Patterson but at another base in the region. She was not a WAC but was a civilian Signal Corps employee working for the Army and the FBI and worked the night shift at a Teletype handling messages and a variety of classified material.

Moseley then presents Miss Y’s story. According to him, she walked into a photo lab run by an Army photographer, referred to as “Mr. Z,” who was developing prints, around a dozen of which were of a saucer. Mr. Z showed her the photos and said he’d taken them during a special assignment to photograph a saucer that had crashed to the north of the base.

“A few days later,” messages came through her station saying that the saucer was being taken through the base, under heavy guard, on the way to Wright-Patterson. She said that she and others in the communications building were informed of the Red and White alert at this time. Two weeks later the alert was ended after those who examined the saucer determined there was no threat. Miss Y and a handful of others were among the few who were aware of the threat, let alone the reason.

Miss Y described the saucer she said she saw in the photos as 30 feet in diameter. She said it seemed to be made of metal pieces that were riveted together. There were no windows visible, but she heard there were windows made of one-way glass that couldn’t be seen from the outside. She said that government scientists had a hard time getting into the saucer and that it was made of, in Moseley’s words, “one or more alloys not found on this planet.” There were no creatures found in this saucer, but she’d heard there were five-foot-tall humanoids found in others.

Moseley wrote that he was convinced that Miss Y was telling the truth about her job, but he would need “three or four” similar accounts to believe that the U.S. government had recovered crashed saucers and little men. He asked Miss Y for the name of Mr. Z, and she reluctantly gave it to him but said that he wouldn’t talk because he was still on active duty.

According to Moseley, after a couple of weeks he talked with Mr. Z in the communications building, and he denied taking pictures of or having any knowledge of flying saucers. Moseley talked with him alone and in the presence of his superior officer.

The men told him that Miss Y did work at the Teletype, but didn’t handle “highly secret” messages except when they were coded, and decoding them was not part of her duties. They said that Miss Y was upstanding and efficient and they couldn’t understand why she would lie about the saucer. From here on, Moseley grapples with the dilemma that has been with UFOlogy from its earliest days, and that is trying to figure out who’s lying and who’s not. According to him, Miss Y told him that the government doesn’t have all the answers and that they hold back information to avoid public panic. In this light, it made sense to him that Mr. Z and his superior wouldn’t confirm Miss Y’s story. He speculates at length on what the government might know and considers the idea that many people might have pieces of the puzzle, but only a few at the highest levels have the whole picture. He wonders when the public will be told and makes a case for disclosure.

Moseley then does something rare among the saucerologists of his day (and those to come) and considers the possibility that Miss Y could be lying. He imagines that she didn’t think that Mr. X would tell someone like him who would actually go out to the base and investigate and that her tall tale to Mr. X had now gotten out of hand. According to Moseley, Mr. Z and his superior were not pleased with her account, and he felt that she might be reprimanded.

According to Moseley, if Miss Y was lying or not lying, Army officials would be compelled to deny her story either way. He ends with this: “Who’s lying? I wish I knew!”