by Charles Lear

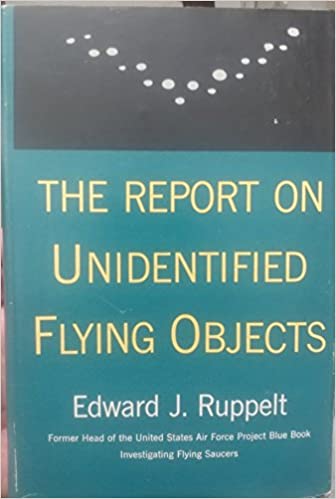

The 1956 book by Edward J. Ruppelt, “The Report on Unidentified Flying Objects” is a must-read for anyone interested in the subject. Capt. Ruppelt was the first director of Project Blue Book after leading a massive re-organization effort to revitalize the investigation while it was still operating as Project Grudge. He was the person who came up with the designation, Unidentified Flying Object, or UFO, which was pronounced “yoofo”, for what were popularly known as flying saucers. His book recounts his time with the project under both names and provides an insider’s view of what were then classified activities. There are two editions of the book with two different endings. The second edition was published in 1960 and Ruppelt included recent cases as a means to update the book. This edition has three more chapters tacked on that have a decidedly more negative tone than the original preceding chapters, where Ruppelt displays an open-minded view. This has led some to wonder if Ruppelt was pressured by the Air Force, which was then following the Robertson Panel’s recommendation to downplay UFO reports.

The 1956 book by Edward J. Ruppelt, “The Report on Unidentified Flying Objects” is a must-read for anyone interested in the subject. Capt. Ruppelt was the first director of Project Blue Book after leading a massive re-organization effort to revitalize the investigation while it was still operating as Project Grudge. He was the person who came up with the designation, Unidentified Flying Object, or UFO, which was pronounced “yoofo”, for what were popularly known as flying saucers. His book recounts his time with the project under both names and provides an insider’s view of what were then classified activities. There are two editions of the book with two different endings. The second edition was published in 1960 and Ruppelt included recent cases as a means to update the book. This edition has three more chapters tacked on that have a decidedly more negative tone than the original preceding chapters, where Ruppelt displays an open-minded view. This has led some to wonder if Ruppelt was pressured by the Air Force, which was then following the Robertson Panel’s recommendation to downplay UFO reports.

A truly remarkable aspect of Ruppelt’s book is that it can be checked against declassified documents. During his time with Grudge and Blue Book, Ruppelt wrote a series of 12 status reports. They consist of descriptions of the efforts made to make the investigation more efficient and scientific along with lists and summations of significant cases. The Ruppelt in the status reports is the same Ruppelt in the book though, understandably, more formal. One gets a sense of healthy skepticism along with an openness to be convinced that UFOs are interplanetary given enough good, scientific evidence.

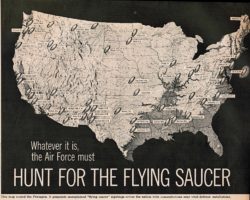

Ruppelt came up against some truly baffling and intriguing cases but the one that likely had the most impact on him was what he called, “The Washington Merry-Go-Round.” Over two weekends in July of 1952, in the midst of a flap that overwhelmed the Blue Book staff, there were a series of radar returns and visual sightings of UFOs over restricted airspace in Washington, D.C. Their behavior was quite mysterious but even so, Ruppelt wasn’t convinced of their interplanetary nature.

Ruppelt came up against some truly baffling and intriguing cases but the one that likely had the most impact on him was what he called, “The Washington Merry-Go-Round.” Over two weekends in July of 1952, in the midst of a flap that overwhelmed the Blue Book staff, there were a series of radar returns and visual sightings of UFOs over restricted airspace in Washington, D.C. Their behavior was quite mysterious but even so, Ruppelt wasn’t convinced of their interplanetary nature.

Ruppelt ends the first edition of his book this way:

“Maybe the earth is being visited by interplanetary spaceships. Only time will

tell.”

His second edition ends this way:

“No responsible scientist will argue with the fact that other solar systems may be

inhabited and that someday we may meet these people. But it hasn’t happened yet

and until that day comes we’re stuck with our Space Age Myth- the UFO.”

The last sentence may not seem that dismissive, but some of Ruppelt’s statements in the chapters leading up to it certainly are. In Chapter 18, he talks about a rumor he’d heard that the Air Force was involved in a conspiracy with the media to “stamp out the UFO.” He assures the reader that his Air Force “buddies” told him that it was business as usual and that there was no “silence” order. He defends the Air Force’s lack of transparency pointing out the manpower required to handle inquiries and that many of those came from “saucer screwballs.” He quotes an officer summing the situation up “neatly” saying, “It isn’t the UFOs that give us trouble, it’s the people.”

Ruppelt also brings up the formation in 1957 of the National Investigation Committee on Aerial Phenomena. With retired high-ranking military personnel on its board of governors and Maj. Donald E. Keyhoe USMC (ret.) as its director, the organization was able to exert influence in high levels of government. Keyhoe was bold enough to write a letter to the Air Force with the suggestion that NICAP’s Panel of Special Advisors be allowed to review the UFO files and evaluate the Air Force’s conclusions. Ruppelt says, “This went over like a worm in a punchbowl.”

Ruppelt’s biggest criticism of NICAP concerns their efforts in getting congress involved when the Air Force chose to ignore them. As a result of those efforts, the United States Senate Committee on Government Operations started an inquiry into UFOs in Nov. 1957. Ruppelt himself was called to testify. He felt the whole thing was a waste of time in the midst of some real problems that were more deserving of attention. According to him, NICAP pounded the deepest thorn of any “into the UFO side of the Air Force.” In spite of this, he defends Keyhoe against accusations that he was seeking publicity and profit through his efforts. Ruppelt felt he was “simply convinced that UFOs are from outer space and he’s a dedicated man.”

Ruppelt’s biggest criticism of NICAP concerns their efforts in getting congress involved when the Air Force chose to ignore them. As a result of those efforts, the United States Senate Committee on Government Operations started an inquiry into UFOs in Nov. 1957. Ruppelt himself was called to testify. He felt the whole thing was a waste of time in the midst of some real problems that were more deserving of attention. According to him, NICAP pounded the deepest thorn of any “into the UFO side of the Air Force.” In spite of this, he defends Keyhoe against accusations that he was seeking publicity and profit through his efforts. Ruppelt felt he was “simply convinced that UFOs are from outer space and he’s a dedicated man.”

In Chapter 19, Ruppelt parades the contactees past the reader. Not mentioned in the book is the fact that he actually attended George Van Tassel’s 1955 Giant Rock Spacecraft Convention and interviewed George Adamski on tape. Adamski does almost all of the talking while Ruppelt remains friendly and civil throughout the over one and a half-hour recording. In the book, Ruppelt brings up the money given to some of the contactees by people who could ill afford it and the death of a woman in the Mojave desert while awaiting contact herself.

Chapter 20 begins with Ruppelt stating outright that he doesn’t believe unidentified objects exist. He points out that that the world had entered the age of satellites since he left the Air Force and that no spaceships had been picked up by the sophisticated tracking systems that came along with it. Blue Book consultant J. Allen Hynek was then the director of an optical satellite tracking program called Project MOONWATCH. He wrote to Ruppelt that they had no records of any unusual objects.

Ruppelt then complains about the expression, “experienced observer.” He points out that everyone is an experienced observer when they see things they’re used to observing. He criticizes radar as being temperamental and points out that operators can be subjective. He then presents a case where military pilots and personnel, along with two psychologists who were Blue Book consultants, all got excited after sighting what turned out to be four weather balloons tethered together.

Insight into possible influences on Ruppelt can be gleaned from correspondence that was preserved from this time. Two letters, one from a member of Ruppelt’s Blue Book staff, Anderson Flues, and one from J. Allen Hynek, were in response to a request for their opinions on UFOs. Ruppelt references Hynek’s letter in the book and Flues agrees with Ruppelt that their investigation did not come up with any evidence that UFOs are extra-terrestrial.

A letter of particular interest is one Ruppelt wrote to Keyhoe in response to an invitation to “work at NICAP.” Ruppelt was then working for Northrop. He declines the invitation and emphasizes that Northrop had nothing to do with his decision. He compliments a NICAP publication, its impressive board, and a statement from a board member, Maj. Dewey Fournet USAF (ret.). He asks about a rumor that a UFO article had been “killed” at the Air Force’s request, says he hopes to get to Washington soon, and will call if he does.

The best evidence that the shift in tone in Ruppelt’s second edition was a reflection of his own beliefs is a letter from Maj. James F. Sunderman. Sunderman had received a memo from Air Force intelligence saying that it was with the understanding that the Air Force would exercise “close control” on Ruppelt’s manuscript that information was being provided for release to Ruppelt. Sunderman’s letter to Ruppelt informs him that he is free to publish the book as written.

While Ruppelt may have not been directly pressured by the Air Force, he confided to his wife that they had expressed displeasure with the book during their NICAP troubles. He served loyally and it is not hard to imagine that, after experiencing the circus around the contactee movement and the repeated waves of overly excited public reaction, he chose to emphasize his increased skepticism and help his brothers out. On the other hand, it’s hard to imagine that, after some of the cases he investigated, he was able to dismiss the mystery entirely.