by Charles Lear

Out of the three most prominent people in UFO abduction research, Budd Hopkins, David Jacobs, and John Mack, only Mack had any formal training in psychology. Hopkins was an artist, Jacobs was an historian, and Mack was the head of the psychology department at Harvard Medical School. Mack’s interest in UFO abduction research first gained major media attention when he co-chaired the Abduction Study Conference at M.I.T. in June of 1992. His position at Harvard lent credibility to the subject, and he worked to convince other academics to consider it seriously. Harvard’s leadership didn’t interfere with Mack’s interest until he published a book in 1994 titled Abduction: Human Encounters With Aliens based on his research with 13 subjects. Mack had had previous success as an author with a 1976 book on T. E. Lawrence, A Prince of Our Disorder, which won him a Pulitzer Prize in 1977. Abduction was a hit and Mack was featured in many newspapers, television news shows, and talk shows. As Mack’s position at Harvard was part of the story, there were some there who felt it was necessary to examine the validity of Mack’s investigations.

Out of the three most prominent people in UFO abduction research, Budd Hopkins, David Jacobs, and John Mack, only Mack had any formal training in psychology. Hopkins was an artist, Jacobs was an historian, and Mack was the head of the psychology department at Harvard Medical School. Mack’s interest in UFO abduction research first gained major media attention when he co-chaired the Abduction Study Conference at M.I.T. in June of 1992. His position at Harvard lent credibility to the subject, and he worked to convince other academics to consider it seriously. Harvard’s leadership didn’t interfere with Mack’s interest until he published a book in 1994 titled Abduction: Human Encounters With Aliens based on his research with 13 subjects. Mack had had previous success as an author with a 1976 book on T. E. Lawrence, A Prince of Our Disorder, which won him a Pulitzer Prize in 1977. Abduction was a hit and Mack was featured in many newspapers, television news shows, and talk shows. As Mack’s position at Harvard was part of the story, there were some there who felt it was necessary to examine the validity of Mack’s investigations.

Ralph Blumenthal wrote a biography about Mack published in 2021 titled The Believer. According to Blumenthal, Mack “had been trying LSD” in 1990 and made an entry in his journal in January of that year trying to find words to “capture the experience.” He was a devotee of the Holographic Breathwork technique, developed by Stanislov and Christina Grof seeking to duplicate psychedelic experiences with yogic practices, and he credited them with opening up his psyche. Blumenthal quotes Mack saying “They put a hole in my psyche and UFOs flew in.”

Mack came upon the UFO subject that same year thanks to Budd Hopkins after becoming aware of his abduction research and meeting with him. Another meeting was arranged for February 17, 1990, in New York. Hopkins invited four people he was working with who seemed to have had abduction experiences, including Linda Napolitano, the subject of the controversial “Brooklyn Bridge Abduction.” Mack was fascinated by their stories and troubled that these people had been overlooked by him and other members of his profession. To him, they seemed to have been traumatized but were otherwise sane. According to Blumenthal, Mack shortly thereafter invited others who had claimed to have had abduction experiences “to an Affect Seminar he was leading at Harvard to explore feelings in the face of traumatic experiences.”

Mack became immersed in his research, which was leading him to a belief that aliens were interacting with us here on Earth, and that belief can be seen emerging in his statements to the press over time. An article (page 2 of pdf) in the May 17, 1992, Boston Herald by Jack Meyers headlined “Harvard Doctor Probes Claims of Abduction by Aliens” quotes Mack saying “I treat it as a trauma of unknown origin.”

A little more than a month later, there is an article (page 6 of pdf) by David Chandler in the June 22, 1992, Boston Globe headlined “UFO Reports Get a Going Over” that mentions Mack’s appearance at the M.I.T. Conference. Chandler gives much of the article over to Mack’s argument that people are having “valid experiences,” and that what he and other researchers are observing is “not some sort of mental aberration.”

It was with the publication of Abduction that Mack went public as a believer that aliens were behind the phenomenon. This stance quickly aroused a good deal of criticism regarding Mack’s methods. A Time magazine article, published within weeks of the book’s release led the way and was so harsh that the leadership at Harvard took notice.

The article by with the headline “Harvard Psychiatrist Claims That Tales of Alien Abduction Are Real. But Former Patients Say His Research is Shoddy,” appeared in the April 1994 issue of Time. Wilwerth’s main source for the story is a woman, Donna Bassett, described as a “Boston-based writer researcher.” According to Wilwerth, Bassett became interested in Mack after “hearing complaints that he was ‘strip mining’ the stories of emotionally distraught people and failing to help them with follow-up therapy.” Bassett read “stacks of books and articles” on UFO abductions and invented a story of her own. She contacted Mack and that led to three hypnosis sessions with him. Along the way, she gained his trust to where he made her the treasurer of his abduction support group.

According to Wilwerth, Bassett made tapes and kept notes “of her life in the UFO cult.” She said that Mack had given her UFO literature to read before the hypnosis sessions that were held in a darkened bedroom in his house and “made it obvious what he wanted to hear.” Bassett also said that Mack billed insurance companies for some of the sessions, claiming they were therapy as opposed to research and that he didn’t provide follow-up therapy for all of his patients.

Mack was given an opportunity to rebut for the Time article, but he found more sympathetic ears elsewhere. An article (page 5 of pdf) in the April 21, 1994, Boston Globe, written by J. P. Kahn, has the headline “E. T. Phone Harvard. Dr. John Mack Could Use the Help as Critics Rip His Research on Alien Abductions,” which sums up the attitude of much of the press and what Mack was facing.

The article opens with a description of the Time article and then gives Mack’s response. According to Kahn, Mack said he expected and even welcomed criticism but “this latest flurry hit below the belt the clinician contends.” Mack said he dealt with Bassett in “good faith” and that if he gave her UFO-related materials to read, “it was only to satisfy her own curiosity about the abduction experience.” He admitted billing insurers for therapy sessions but said that all the money, $2,000 to $3,000, went to the Group for Research and Aid to Abductees.

Mack had formed a group, The Program for Extraordinary Experience Research in 1993 to oversee his abduction research. A spokesperson for PEER, Karen Wesolowski, said that Mack had stopped treating abductees as private patients and stopped billing insurance companies, in Kahn’s words, “in order to be ‘absolutely scrupulous’ about the clinical division between research and therapy.” As for the people who complained about their experience with Mack, Mack is quoted saying “How can I possibly keep everybody happy? There are bound to be one or two disaffected people. That’s what I object to, the focus on them.”

According to Blumenthal, two months after the Time article was published, Mack, feeling the need to “clear the air with Harvard,” made an appointment with S. James Adelstein, the executive dean for academic progress. When he got to Adelstein’s office on June 1, 1994, Adelstein handed him a letter.

The letter was dated the day before and informed Mack that the staff at Harvard had received “several inquiries” regarding his alien abduction research “that relates to protocol formulation, informed consent, and patient billing.” In response, Harvard Medical School was putting together a committee to review his work in abduction research.

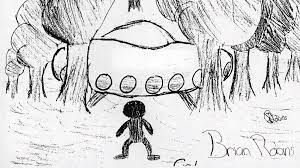

Both parties agreed to secrecy for the duration of the review. In the meantime, Mack visited the Ariel School in Ruwa, Zimbabwe, and interviewed children there who claimed they saw one or more silver craft land in a field. Some said they received telepathic messages from black-clad aliens about taking care of Earth’s environment.

Both parties agreed to secrecy for the duration of the review. In the meantime, Mack visited the Ariel School in Ruwa, Zimbabwe, and interviewed children there who claimed they saw one or more silver craft land in a field. Some said they received telepathic messages from black-clad aliens about taking care of Earth’s environment.

Almost a year after the beginning of the review, news of it got out, and there is an article by Lana Israel in the April 17, 1995, Harvard Crimson headlined “Mack’s Research is Under Scrutiny.” According to Israel, the person likely to have been responsible for the leak was Mack’s former lawyer representing him during the review, Daniel Sheehan. Sheehan reportedly sent letters out to people in the UFO community in an effort to muster support. George Lamb, “an associate of one of Mack’s benefactors” is quoted as saying “I understand that Sheehan had spoken out of turn and their company parted.”

Reaction to Sheehan’s mailing is presented ranging from UFO lecturer/researcher Stanton Friedman saying “The notion that Mack shouldn’t study the area is what I consider a ‘witch hunt.’” to Robert Baker, emeritus of psychology of the University of Kentucky saying, “I don’t think anyone is trying to shut him up, but trying to see if he has not lost touch with reality.”

An article by Christopher Daly in the August 4, 1995, Washington Post headlined “Harvard Clears Best-Selling UFO Author” reports that officials at Harvard had announced earlier that day that they would not discipline Mack. “Instead, Dean of the Harvard Medical School Daniel Tosteson met with Mack and reminded him of the standards expected of a Harvard professor. At the same time, however, the dean reaffirmed Mack’s right to study whatever he wishes.”

Mack’s lawyer said that “the outcome was a relief to Mack” but added that “it hardly made up for the stress, lost time and $100,000 in legal expenses” incurred during the process. Mack continued with his work on abductees and published Passport to the Cosmos: Human Transformation and Alien Encounters in 1999. Then, on September 27, 2004, while in London, England, to lecture at a conference sponsored by the T. E. Lawrence Society, he was struck and killed by a drunk driver. He was 74.